Reflective supervision is often described as serving three functions: developmental, normative, and supportive; although there is no one definition.

Group supervision models tend to rely on an experienced facilitator, particularly if one is to follow the Integrated Developmental Model of Supervision. As practitioner psychologists, we are clear on the importance of supervision in maintaining and developing our professional practice.

Professional bodies across psychology professions including the Health and Care Professionals Council (HCPC) and the British Psychological Society (BPS) have criteria about the amount of supervision that is required to continue practicing. For staff in schools however, this is not something that is clear.

Professionals within schools are required to teach and support children, every day, often with presenting needs including complex developmental needs and developmental trauma.

It is also important to consider the context in which teachers are working. The pandemic has had long lasting effects, putting pressure across school systems, there have been teacher strikes about effective pay decreases and, children are presenting with higher levels of mental health. With all this in mind, there is a case to be made for the importance of supervision for those working in educational settings.

The evidence for this is shown through teachers leaving the profession faster than ever before, with one study finding the rate to be 50% having actively sought to leave the profession in 2022.

At Camden Educational Psychology Service we have been working on an organisational project to embed trauma-informed practice in educational settings.

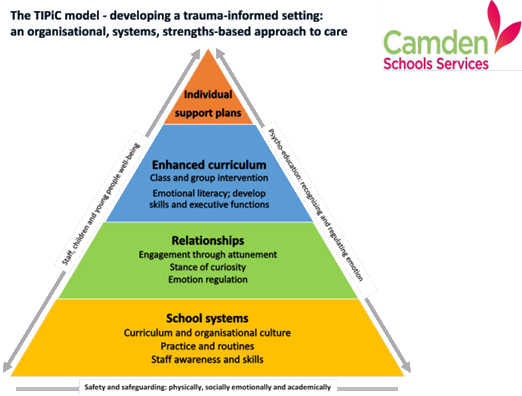

Trauma-informed project in Camden (TIPiC) is a multi-agency approach supporting schools to support and, most importantly, embed trauma-informed care across all levels. The model, displayed below, aims to develop an organisational and strengths-based approach to care.

The TIPiC model.

As part of the TIPiC project, senior leaders overwhelmingly chose staff wellbeing as an area they prioritised.

In literature around trauma-informed care, we know that the ‘containers need containing’ to effectively support and care for others, but the extent of the need in schools was striking.

As a result, educational psychologists working in these settings implemented better peer supervision sessions and found it to be one of the most effective and valued part of the support for staff in schools.

Since the sessions have been implemented it has allowed staff to be better attuned to children and young people’s needs.

Below are some of the key things we have learnt so far:

Gaining information using standardised measures, from staff members prior to the peer supervision sessions has allowed for tailoring the sessions for the particular staff group.

Setting up a ‘wellbeing group’ of staff members to focus on wellbeing of the staff team and how peer supervision is a key element within this.

Sessions worked best when the time of day worked best for staff members (i.e. not during a busy time). Senior leadership often needed to prioritise the sessions over other responsibilities and allow time for staff to easily attend. Sessions worked best when organised on the same day and time and at regular intervals.

School staff have required ground rules (albeit minimal) around confidentiality and behaviours during sessions, overtly stating these and reminding the group of them before each session.

Within this project each facilitator is an educational psychologist and therefore has training in running group supervision sessions. Each group required highly skilled ways of managing the group dynamics and reflecting on these to adapt the process. For example, if one member of the group is particularly vocal, considering how to ensure that others are able to contribute equally.

A key part of this work, is to skill up the setting to continue peer supervision and therefore the educational psychologist had to identify staff members who could take on the facilitator role and continue the sessions after the intervention. Role modelling behaviours and the group experiencing the process have also been key to ensuring that the group can continue a peer support structure into the future.

By providing effective supervision it has allowed staff to be attuned to children and young people’s needs. The impact of this approach has been:

- Increased feeling of being valued.

- Knowing how and when to access support from others outside of the sessions.

- Upskilling of ‘reflection skills’.

- Understanding of self and increased skills in managing own needs.

- Becoming more familiar with group supervision processes and using sessions more effectively.

Qualitative and quantitative data gathered during this project has shown clear impact.

By providing effective trauma-informed supervision - long-term, systemic support for schools is supporting them in making clear differences for pupils, staff and parents.