There is a strong emphasis on ‘shared and equal responsibility’ between statutory partners – local authority, integrated care boards (ICB) and the police – in overseeing and delivering multi-agency safeguarding Local Child Safeguarding Practice Reviews (LCSPRs). The Child Safeguarding Practice Reviews Learning Support Project set out to explore the experiences of policing and health professionals because less is known about the perspectives of colleagues working in this area.

Two focus groups with police professionals (working at a strategic and operational level) explored:

- The structures and governance in place.

- The police contribution in the LCSPR and Rapid Review process.

- Police expertise, capabilities and skills for engaging in reviews.

Whilst the LCSPR process is a statutory multi agency function, in practice, the design and shape of LSCPR processes, is led by local authority. In this blog, we reflect on how police are required to configure around the process, to make it work. We start to consider the implications for how well the process is working from a policing perspective.

Police and ICBs, have fewer dedicated specialist roles at a local level, and practitioners and strategic leads often have additional responsibilities, outside of their safeguarding role. Consistency, capability and capacity to attend meetings is more challenging than perhaps local authority, who have dedicated resources, including the business unit function, that typically organises the review process.

Police structures: How policing interacts with local safeguarding arrangements and LCSPRs

Before we share what police colleagues talked about in the focus groups, it is worth looking at police structures and roles.

Geography is an important contextual factor for strategic safeguarding leaders and practitioners alike. Working Together 2023 states:

Although the geographical boundaries for the three safeguarding partners may differ in size, multi-agency safeguarding arrangements should be based on local authority areas.

4.1 Chapter 2, Working Together 2023

ICB and police geographical boundaries are rarely coterminous with those of local authorities.

This creates an inevitable tension within the safeguarding system, where policing’s strategic requirement for consistency, capacity, and capability at a force level might not always have the flexibility to meet bespoke place-based safeguarding arrangements.

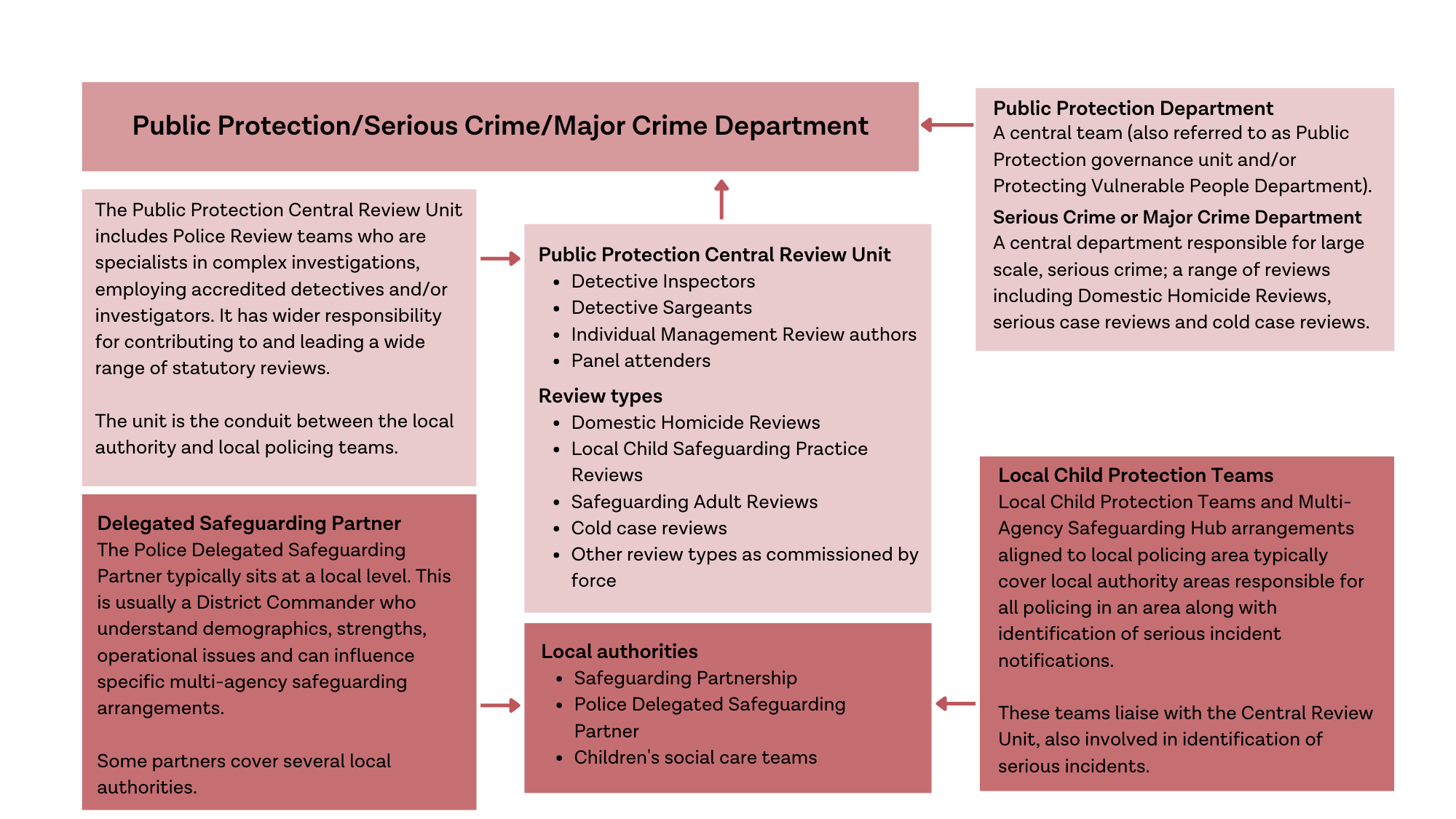

Typical structure of Police Public Protection Central Review Unit and relationship with local policing.

Police contribution: How well police interact with the LCSPR and Rapid Review process

So, looking at this diagram, we can see that police forces have introduced structures that enable the police service to fulfil force requirements and local safeguarding arrangements.

Police forces, typically manage all types of serious case reviews, within a Central Review Unit (the light pink boxes), often referred to as a central governance unit or as ‘the centre’ by police. This can include Domestic Homicide Reviews (DHR) Local Child Safeguarding Practice Reviews (LSCPR), and Safeguarding Adult Reviews (SAR).

But local teams (in the red boxes) are where the Delegated Safeguarding Partner – usually a District Commander – police child protection teams and local police practitioners sit. These professionals are usually involved in decisions about making Serious Incident Notifications with health partners and the local authority (the duty to notify rests with the local authority). They are more involved in the circumstances that lead to reviews and will better understand the context and learning. The local policing teams interact with the local Safeguarding Partnership.

In the focus groups, we wanted to understand:

- Are the police structures enabling the right levels of engagement and ownership with child safeguarding review processes?

- How well do central review teams connect with local policing and Local Safeguarding Partnerships?

The focus groups discussed:

We heard that it is important that there is connectivity between local and central police teams when it comes to engaging in review processes:

- A Public Protection Central Review Unit provides dedicated staff who understand and attend key LCSPR processes, like, multi-agency panels and learning events. But there is a risk that the realities of everyday operations and challenges are not fully reflected in review processes as they are disconnected from local authority teams and policing teams.

- The Central Review Unit at force level provides oversight of all LCSPRs. This was seen as valuable as they have capability to provide specific data and insight into force wide issues and reoccurring recommendations. For example, information sharing, cumulative harm and cross cutting themes such as domestic abuse. Whilst frontline officers may not have the expertise to discuss force-wide safeguarding policies.

- Frustration with lengthy delays due to parallel criminal proceedings was expressed. Delays required additional coordination and explanation as the Central Review Unit acts as a conduit between the investigation team and the review process.

- Practitioner experience of the system is important, therefore central representation at local practitioner events, means that local police professionals are not directly involved. Views were expressed about the benefit of practitioners and the central review team jointly attending events.

- Some practical activities are seeking to strengthen the links between central review teams and local safeguarding leaders (DSPs). One force area is implementing a strategic post that provides a link between the central review team and delegated safeguarding partners at a local level.

It was suggested that there are opportunities to strengthen police oversight and engagement into reviews at a regional level:

- The issue of geography is more challenging for police and ICB LSPs, who are accountable for multiple LA safeguarding partnerships across a region. Lead Safeguarding Partners are Chief Executives of ICBs, Chief Executives of Local Authorities and Chief Officers of Police.

Discussions raised questions about whether there is a multi-agency gap at a regional level. Participants were interested in:

- How regional learning could be better coordinated and expanded across partnership arrangements.

- Possible benefits of commissioning thematic and regional reviews.

Police knowledge and expertise: How are police equipped to participate and deliver review processes?

When we asked focus group participants about relevant knowledge and skills, the conversation focused more on the LSCPR process. The groups discussed:

- Police have limited training and understanding about review methodologies, such as systems thinking and appreciative inquiry. An absence of multi-agency professional development, may partly explain why policing defaults to an investigative mindset.

- There is a focus on ensuring officers comply with policy and procedures, and a preference for structured templates, like those used for individual management report (IMRs).

- Some forces recruit non-police staff to provide a broader range of skills, knowledge, and perspective in the analysis required to undertake successful LCSPRs.

- There are competing priorities between different types of review. A scoping of professional development requirements for review teams by the Vulnerability Knowledge and Practice Programme (VKPP) for policing found that review officers are often expected to undertake cold case or live investigation reviews, as well as statutory case reviews. Statutory reviews such as LSCPRs and DHRs may get less attention and priority.

Overall, the skill sets required to undertake the different review types needs to be considered more by policing.

- Undertaking work for a statutory review process is very different from investigation reviews and requires a different way of thinking and writing.

- The College of Policing is currently looking at how to ensure police professionals are equipped with the skills they need to undertake and participate in review processes as part of a wider programme to professionalise public protection.

An opportunity to strengthen the ways in which the police contribute to review process

The focus groups have prompted police professionals involved in the project to think more about:

- How to maintain connectivity between local policing and central review teams.

- Involvement in reviews is ‘too central’ and lacking local policing experience and context.

- Are local staff lacking experience of safeguarding review processes and its intention to impact on system changes.

- Is there a gap across the system in professional development and multi-agency training, and what’s needed to support and engender a shared approach and ethos to reviews.

- The potential for thematic reviews providing rich learning for systems issues, which might not surface through the lens of a particular case review.

- Opportunities and efficiencies in sharing statutory LSCPR agency data, and the coordination of multi agency learning at a regional level.

- The requirements to identify and solve persistent problems at a regional level, and how that is aggregated to a national level and prioritised (for example IT enablers/ barriers for information sharing/accommodation provision etc).

We have reflected on the differences between agencies informing how they engage and relate to the purpose of LSCPRs. For example, in the focus groups, we noticed that:

- Professionals representing health services and the ICB might be more focused on a need to see the human experience, the child, the child’s family, and secondary trauma experienced by practitioners.

- Local authority colleagues are possibly more confident with systems thinking and strengths-based learning.

- Whilst the police we talked to spoke about a bias towards an investigative and compliance mindset.

This poses questions about differing cultures in agencies, influencing how they fundamentally approach LCSPRS, including how well they understand and invest in the core purpose of reviews, as a driver for learning and improvement.

Focus groups emphasised the need to pay more attention to differences between agencies and opportunities for multi-agency safeguarding partnerships.

In the absence of a developed multi-agency ethos, single agency expectations about the aim and impact of LCSPRS are likely to differ. Working Together 2023, has moved us into an era of joint and shared responsibilities. This may not mean however, that we do things the same. It may mean we need to pay more attention collectively to our differences.

What do you think?

- Should we be explicit about the different perspectives and capabilities across the statutory partners with responsibility for reviews? What would this help to achieve?

- What can we learn from professionals in police and health, who have a bird’s eye view of multiple LCSPRs across a region?

- What would we need to do differently to enable all agencies to have a sub or regional response? Could it present new opportunities for learning and development?

This project is a collaboration between Research in Practice, the University of East Anglia and the VKPP (Vulnerability Knowledge, Policy, Programme). The VKPP is a national policing programme within the College of Policing, and uses academic and wider research, to co-ordinate and enhance the Policing response to public protection and vulnerability. The VKPP have been undertaking their own police - specific research on LCSPRs/serious case reviews for over six years and have internal expertise on police-specific learning.