At Research in Practice we are passionate about evidence-informed practice.

We aim to bring together research, practice expertise, and the experiences of people with lived experience to produce resources and learning opportunities tailored to the learning needs of different roles across the system. Everything we offer is designed to equip individuals and organisations with the knowledge, skills and confidence to apply evidence in their work, and thereby to enable people to live good lives.

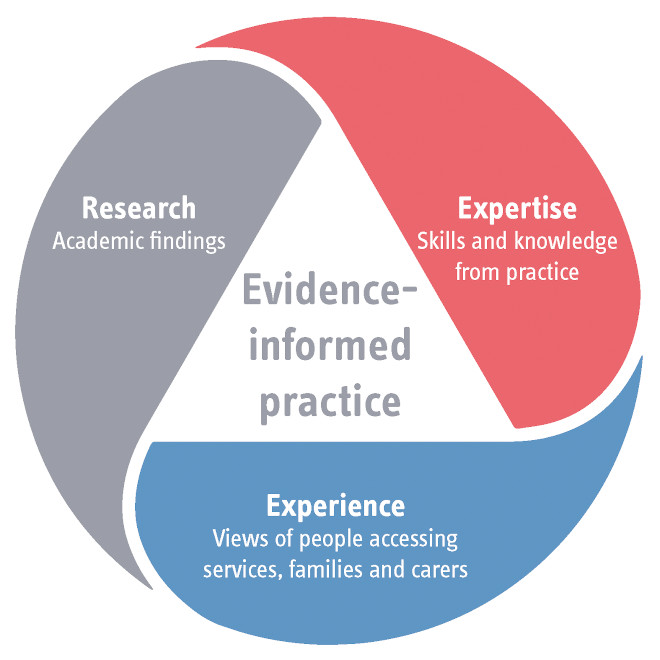

Our work brings together research evidence, practice expertise and the lived experiences of people accessing services.

Why evidence-informed practice matters

In working with people, whether directly or in leadership roles, it’s vital that our practice is ethical, defensible and has the best chance of being effective. We aim to support this by enabling evidence-informed practice. This means ensuring decision-making is informed by:

-

the views and expertise of the people being supported

-

robust relevant research and data

-

professional wisdom and

-

local or individual contexts.

Drawing on evidence from multiple sources

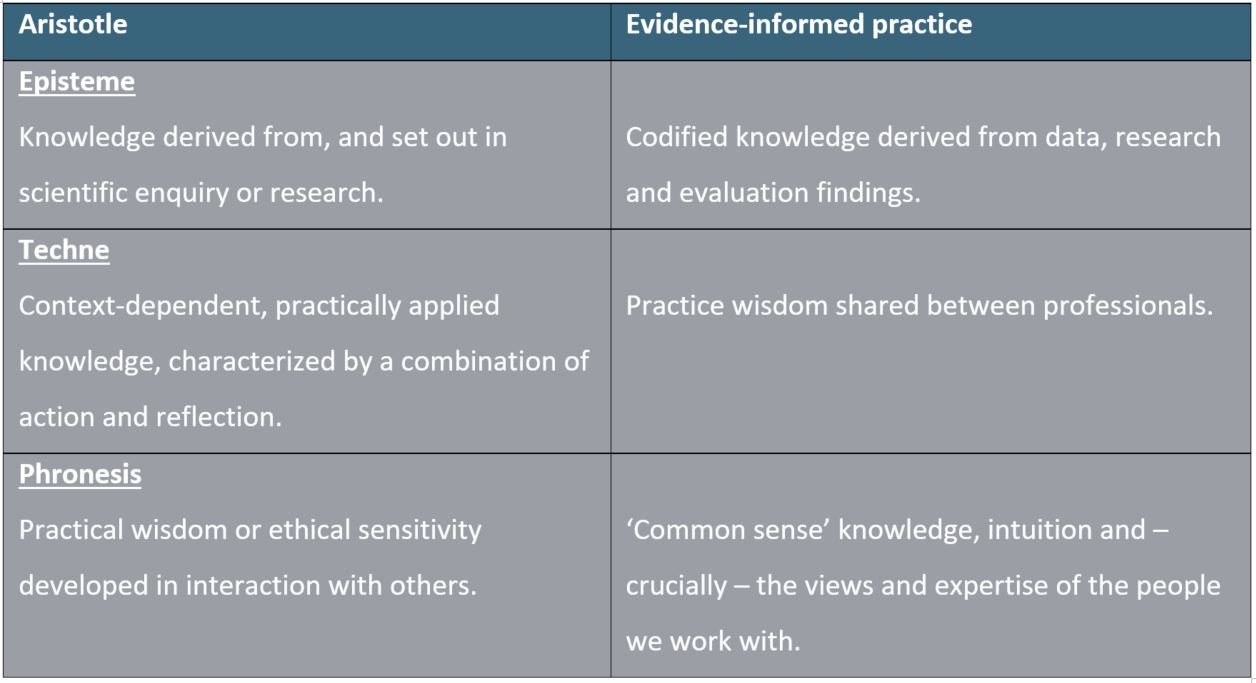

Research evidence is a crucial ingredient within evidence-informed practice, but other sources of information and knowledge are vital too. Throughout history knowledge has been defined and categorised in different ways – in fact, we can map Aristotle’s definitions of 1700 years ago against the types of knowledge that make up evidence-informed practice (adapted from Avby et al 2017):

Types of knowledge that make up evidence-informed practice (table adapted from Avby et al 2017).

Recognising power and complexity

Philosophers have argued for centuries over these definitions and the power dynamics they reflect. For us, being ‘evidence-informed’ differs from being ‘evidence-based’ or ‘research-based’, not only because it explicitly involves drawing on multiple sources but also in that the intention is to actively disrupt traditional power relationships between different forms of knowledge, and so promote a more inclusive equalities-aware model of evidence use.

Rather than focus only on the ‘application’ or ‘transfer’ of research evidence to practice we aim to enable the interplay between different forms of knowledge in local context and across our national networks. This focus on real-world context is well summarised by Greenhalgh and Papoutsi:

‘The gap between the evidence-based ideal and the political and material realities of the here-and-now may be wide… The articulations, workarounds and muddling-through that keep the show on the road are not footnotes in the story, but its central plot. They should be carefully studied and represented in all their richness’

(Greenhalgh and Papoutsi 2018, p2)

Just as we want people being supported to be active partners rather than passive recipients of services, so too should we aim to enable professionals to be engaged actively in the generation and use of evidence. Each source of knowledge – research, practice wisdom, and lived experience – inform and interact with the others. This circular process aims to:

-

Ensure what we produce is meaningful and relevant.

-

Increase the impact of useful evidence in practice contexts.

-

Help professionals to actively engage with the people they support in developing and improving practice.

Getting practice into evidence

‘If we want more evidence-based practice, we need more practice-based evidence…’

(Green, 2008)

Sometimes practitioners or the people they serve can feel that research is detached from their lives. But where research is rooted in issues that matter most to practitioners and the people they support, this can support engagement and use. Engaging people with lived experience of social care, as well as professionals working in the field, as early as possible in evidence generation activity, is central to helping research to resonate.

Practice-informed evidence can be promoted through activities such as:

-

Co-productive and strengths-based approaches to research design.

-

Engaging people in sense-making activity to contextualise research findings.

-

Creating roles that span practice and evidence generation.

-

Enabling people receiving and providing support in dissemination activities.

At Research in Practice, we try to support practice informed evidence by engaging our Partners at every stage of our offer – from topic selection to contributing to publications and events, to reviewing outputs to ensure relevance.

Implementation is relational, not only transactional

Relationships are at the heart of supporting children and adults, and so it follows that they are central to how we support those working in the sector.

We are passionate about shaping people’s relationship with evidence – not to simply increase the readership of academic research – but to promote active engagement, co-creation and capacity building.

Drawing on the work of academics who specialise in evidence use and knowledge implementation, it is clear that relationships are a key part of enabling evidence-informed practice:

-

The role of Knowledge Brokers – individuals positioned at the interface of research and practice – has been identified as important. These people act as negotiators, translators and can be the ‘human force behind knowledge transfer’ (Ward et al, 2009) and they need support to do this well.

-

The personal motivation and values of knowledge mobilisers matter: their enthusiasm, commitment, courage and creativity, are all noted as important qualities (Phipps & Morton, 2013).

-

Within implementation research, high-quality relationships between those supporting implementation and those providing services was identified as ‘a—if not the—critical factor for achieving implementation results’ (Metz et al, 2020).

-

For organisations seeking to embed evidence utilisation, passive dissemination of evidence is shown to not be enough. Interaction; social influence; facilitation; incentives and reinforcement are all key (Nutley et al, 2007; 2009)

All of this highlights the need for a relational approach, and emphasises the need for collaboration between those generating, using, and benefiting from evidence. This thinking underpins our Link Officer model, informs our Change Project methodology and drives our collaboration with the academic community.

A multi-layered approach to evidence-informed practice

At Research in Practice we aim to build the sector’s capacity for evidence-informed practice, so that professionals can be mobilisers of knowledge, rather than recipients. Research has shown that when evidence-informed practice is adopted across a whole organisation and incorporates a range of approaches, it is likely to be more successful. (Gray, et al, 2012).

This is why we work to support sustained use of evidence at all levels – from direct practice, through to first-line management, strategy development, commissioning and policy. This requires a systemic approach, with outputs complementing each other. This is why we develop products and learning opportunities that are stratified for different roles and use a variety of different approaches within our 360 offer.

References

Avby, G. et al. (2015). Knowledge use and learning in everyday social work practice: A study in child investigation work. Child & Family Social Work: Wiley.

Gray, L. et al. (2013). Implementing Evidence-Based Practice A Review of the Empirical Research Literature. Research on Social Work Practice: SAGE Publications.

Green, L. (2008). Making research relevant: if it is an evidence-based practice, where's the practice-based evidence? Oxford University Press.