Defining community

What this means

When ‘communities’ are discussed, it is often in a narrow way. When thinking about ‘communities where everyone belongs’ we need to think both about physical and/or geographical communities (where people live, and may or may not have things in common) and ‘communities of interest’ (where, by definition, people share a wide variety of interests, worldviews, activism, culture, religion, and an almost infinite number of other permutations). You may also think of your own communities of practice in the work you do, and how valuable they are to your professional resilience.

People can belong to many different types of community, and these communities help make up people’s individual identities.

We need to work towards a new definition of community. What’s your personal definition of community?

The research

Communities – whether geographical, ‘communities of interest’ or communities of practice – are complex and don’t always have one meaning. The same community can be seen very differently by different members within it; communities can also evolve, with a network of shifting relationships and resources (Sutton, 2017; Leaney, 2021).

This very complexity can be a source of strength. The 'social infrastructure’ within communities – where relationships are formed and maintained – can lead to innovative use of space - for example, with communities both defining their own issues and formulating their own responses (British Academy/Space To Change, 2023). Working positively with communities is different to ‘providing services’ to a community – it’s about promoting engagement and empowerment rather than meeting a need.

At their heart, communities often have values of reciprocity and mutuality. Reciprocity is when people get something in return for their efforts. Neighbours or people with a shared interest might do things in return for each another, sharing their skills or abilities. Mutuality is where people do something together, such as work on a community project, and this can bring indirect benefits to a community relationship, such as a sense of achievement and comradeship (Sutton, 2017).

Sometimes, when thinking about communities of interest, people who share an interest live close to one another – but, often, they don’t. The internet facilitates communities all over the world (this is explored in more detail in the theme Access (Technological)). However, when people can travel to be physically close to communities of interest, they often will.

Bonetree (2022) looked at older people’s ‘dispersed communities of interest’, including faith and culture-based communities of interest of many different heritages, and found that people make great efforts to travel to see their fellow community of interest members. These mutually-supportive communities of interest were important in helping Manchester’s aim to be an age-friendly city. However, such local communities of interest are not always self-sustaining - the study also found that they were, in turn, supported by local grassroots organisations, and that these organisations could themselves be vulnerable to reductions in funding (Bonetree, 2022). This is explored in more detail within the Supporting Community Organisations theme.

Communities of practice have been defined as ‘groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interaction on an ongoing basis’ (Wenger et al., 2002). Communities of practice in social care have been associated with the development of understanding and skills, collaborative working and problem-solving, and being part of a wider learning organisation (Staempfli, 2020). It has also been argued that they support practitioner resilience when facing complex issues (Goglio-Primard et al., 2020).

There are limitations in the overall research picture around communities. This is partly because communities are as unique as the people who form them, so it can be difficult to pull out wider generalisable messages from individual research studies. In addition, there is an abundance of small-scale studies and ‘grey literature’, making it difficult to find and assess the effectiveness of initiatives. However, the overall research picture is generally positive about the power of both geographical communities and communities of interest, providing suggestions for how communities where everyone belongs can become a reality through patience, co-production and power sharing.

What you can do

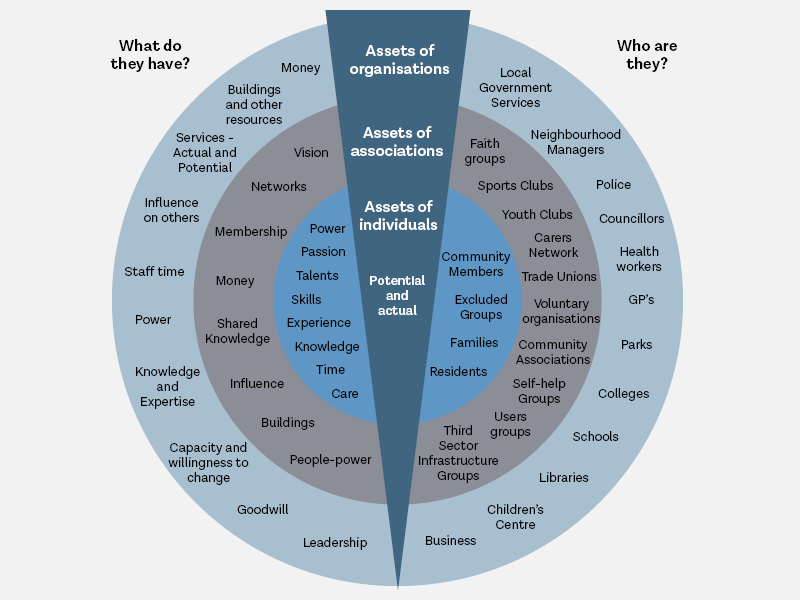

If you are a senior leader or commissioner: The Care Act 2014 requires local authorities to ‘consider what services, facilities and resources are already in the area and how these might help local people’. Field and Miller (2017) created a graphic that illustrates the rich variety of what these services, facilities and resources might look like.

(Field and Miller, 2017; quoted in Sutton, 2020)

Look at the graphic above and consider the assets in your local community plus the potential of ‘communities of interest’, which may exist over a wider geographical area. What are the strengths? Where are the gaps?

In addition, the research brings out how important it is for people to remain connected to communities of interest. As Bonetree (2022) put it: It’s about people, not just place. The research also highlights that people are willing to travel distances to be part of their communities of interest.

- What is already in place to facilitate travel to communities of interest?

- Where are the gaps? For instance, is there only one model (such as concessionary transport) in place?

- Are there ways to link up strengthening communities with environmental work via affordable and sustainable transport?

If you are in direct practice: Be curious about people’s communities and don’t make assumptions. While people may live in a certain area, they may consider their community of interest to be elsewhere - in some cases in a completely different country. You could consider asking people:

- What does community mean to you?

- What communities do you feel like you belong to (encourage thinking about both geographical communities and communities of interest)?

- Do you need support to continue or strengthen your community ties – and, if so, what type of support?

If you are noticing patterns in terms of people’s community ties (such as to a particular group or centre) this is worth a wider discussion in your team. Your team can then consider how it can strengthen your organisation’s ties with these vital community links, and support the work they do.

Further information

Read

Think Local Act Personal has a guide to ‘transforming conventional into asset-based practice’, which provides an overview of community co-production.

The Practice Supervisor Development Programme has a Practice Tool on Developing a community of practice in your organisation.

Listen

Research in Practice has three podcasts on ‘Love Barrow Families’. Although the context is work with families and children, the experiences offer much learning for adult services – thinking about geographical and social context, the importance of relationships, and an honest discussion of challenges as a dynamic community organisation with limited resources.