Disruption

What this means

The language of ‘disruption’ is often frowned upon. Why? Disruption, in the sense of disrupting the expected way of doing things, is seen as positive in commercial spaces. It is only through disruption that change occurs.

When people know and understand the issue, they can often find the best and most creative solutions. It’s not about services being presented with unachievable demands by their citizens - but about working together to arrive at workable solutions.

Ideas that may seem initially too hard, too unusual, or too ‘disruptive’ are likely to have at least something in them that’s doable. Don’t only think of the risk in doing something new within communities; think of the risk of not doing anything, and in carrying on with business as usual. Ensuring people and grassroots organisations are equal partners in existing power structures, such as Integrated Health and Care Boards, are vital for allowing the conditions for disruption to exist.

Communities have the power to effect change, but it can often feel like they don’t.

The research

Communities are uniquely placed to identify their own problems and create their own solutions (Durie & Wyatt, 2013). This is not likely to align exactly to what local and national policymakers think are the problems and solutions – so co-production is of vital importance in ensuring community needs are met in a way valued by citizens.

The conditions for disruption are also founded on the values discussed in the Sharing Power As Equals key change (particularly within the pre-produce, co-produce, evaluate section). O’Shea et al. (2019) found that, in patient and public involvement groups, hierarchies existed, with some professionals and public members afforded more scope for influencing service development than others, and where ‘public and lay members could not have as much input to commissioning decision-making as they believed was or should have been possible’ (p.6). If people don’t feel like their voice is heard, disruption is less likely to occur.

Risk aversion can become embedded as a way of working in local authorities. As Nesta (2020) puts it, ‘…the idea of risk avoidance and aversion has become a dominant and crucial feature in the way public services are designed, managed and reviewed. Public servants are often tasked with managing the possibility of something bad happening, and services are designed to respond to and mitigate against these negative risks’ (p.6).

In direct practice, risk enablement (instead of risk aversion) is seen as part of strengths-based practice and is a way of working that’s aligned with human rights and self-determination (Nosowska, 2020). Risk enablement recognises that supporting people to take carefully-considered risks – rather than seeking to avoid them – can lead to better outcomes for people, and is an ethos that has underpinned Making Safeguarding Personal. One reason that risk enablement is valued so highly is because ‘taking risks can engage positive collaborations for beneficial outcomes’ (McNamara & Morgan, 2016, p.3).

There are parallels between this kind of direct positive risk-taking and the kind of risk-taking, or disruption, local authorities can take in their wider work with communities. Nesta (2020) argues that innovation in local authorities can be seen not as ‘risky’ but, in fact, as reducing risk – because it encourages partnership and trust between local authorities and communities, where ‘trusting people to innovate, explore and learn from what goes wrong, as well as what goes right, is enabled by a more mature and nuanced conversation about risk appetite’ (p.18). Therefore, taking the principles of risk enablement in direct work – understanding that risk can never be completely eliminated – can be a helpful starting point in wider community work, too.

What you can do

If you are a senior manager: Think about how risk, disruption, and innovation are seen in your organisation. You might reflect on how far the following are true:

- Culture and values drive decision-making, rather than processes.

- Learning, experimentation and curiosity are prioritised in service delivery.

- Decision-making is devolved to those closest to the people affected by the decisions, and both staff and citizens are trusted to take appropriate action.

- Psychological safety is prioritised, creating a culture where it is safe to innovate, take risks, fail, and learn.

(Adapted from Nesta, 2020).

Another useful way of looking at embracing disruption is the idea of ‘Red Ocean’ and ‘Blue Ocean’, a term coined in the business world by Chan and Kim (2004). This is the idea that you should ‘go where the competition isn’t’ – that the red ocean is crowded, fighting for a diminishing market share, but the blue ocean isn’t, and this is where the true opportunities lie. What are the possible ‘blue oceans’ in your community – areas of demand, or potential demand, where you could create something different where nothing is happening?

The Communities Where Everyone Belongs group strongly felt that local authorities had very little to lose by adopting organisational mindsets built on trust, innovation and disruption. There was often the sense that organisations felt fear, rather than excitement, about disruption and innovation.

Simple ideas for increasing innovation might include always ringfencing 5% of a budget for something new; or ‘blue sky thinking’ sessions where senior leaders can get together with all in the organisation, and create conditions where they can be challenged and hear new ideas from everyone.

Why should we embrace disruption?

In this clip, Bob Jones explains why we should embrace disruption:

Further information

Read

Nesta’s publication, Reframing Risk, can help local authorities innovate and disrupt in their work with communities.

Research in Practice has a frontline briefing on Risk enablement – which helps link organisational and practice approaches to risk.

Engage

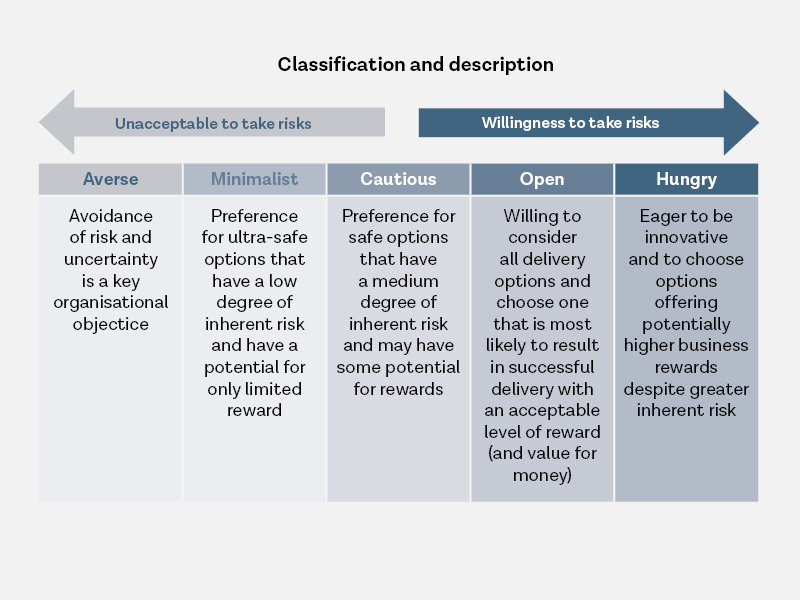

Denbighshire Council has developed a ‘risk appetite framework’ which they use to plot the organisation’s own appetite for risk in different areas such as finance, reputation, policy delivery, and so on. The categories they use are:

You can read more about Denbighshire’s work in the appendix to Managing Risk for Better Service Delivery.