Social work as a resource

What this means

The values that citizens appreciate in social workers – particularly of relationship-based practice, helping maintain independence, and preventing future needs developing – can feel squeezed due to the pressure people are working under, and as workers are forced to focus more on crisis management.

Listening to what people say, and standing up for their rights, is invaluable to people with care and support needs. The shift from ‘doing for’, and ‘doing to’ people towards ‘doing with’ is all about social work being an enabling, empathetic profession. This type of approach is often the reason why social workers were drawn to the profession – and these qualities need to be supported by the organisations they work for.

'Doing things with me is the modern-day kind of support from social care staff that gives me a degree of choice and control, and enables me to enjoy an interesting life.'

The words of one group member.

'Social workers should be seen as an investment by the system, and there should be time and effort invested to keep them. It’s investing to save.'

What are some of the most important things a social worker can do?

In these videos, Cath Sorsby, Susan Bruce and Kadie Chapman reflect on the role of the social worker and describe some of the most important things a social worker can do which includes co-production:

The research

As set out by The British Association of Social Workers (BASW)’s Code of ethics, ‘Human rights and social justice serve as the motivation and justification for social work action. In solidarity with those who are disadvantaged, the profession strives to alleviate poverty and to work with vulnerable and oppressed people in order to promote social inclusion. Social work values are embodied in the profession’s national and international codes of ethics.’ The Professional standards for social work also set out that social workers must ‘…promote the rights, strengths and wellbeing of people, families and communities’ and ‘…establish and maintain the trust and confidence of people.’

This is very similar to what some people with care and support needs say they value in social work. According to Peter Beresford (2012), in his research on what people want in social work, people ‘talk of relationships based on warmth, empathy, reliability and respect’ and about social workers as ‘friends, not because they confuse the professional relationship they have with them with an informal one, but because they associate it with all the best qualities they hope for from a trusted friend.’ Beresford also highlighted that people value the combination of practical and emotional support in social work, because it is through sorting practical issues out that people ‘can build the trust and confidence to confide in social workers, and be in a position to gain emotional strength from their support’ (Beresford, 2012).

So, if both social workers and people with care and support needs value very similar things, what is stopping the development of this productive relationship? One reason may be that the role of social work is not only to build relationships and empower people but has also developed into a ‘gatekeeper’ of resources, particularly as social care resources have become scarcer following austerity in the UK (Pentaraki, 2016; Grootegoed & Smith, 2018).

Research looking into the impact of austerity on social workers has found that having to limit contact or gatekeep services is experienced as a breach of ethics, which may often manifest in social workers having to bend the rules or do (often unpaid) overtime to provide what they believe to be an acceptable level of support (Grootegoed & Smith, 2018; Aronson & Sammon, 2000; Pentaraki, 2016).

Grant (2013) found that the empathy needed to provide those aspects of social work so valued by people with care and support needs, also held the potential to affect social workers themselves. Workers had to be empathetic to do the job, but this could leave workers open to ‘empathetic distress’, where they may experience secondary trauma and personal upset. 'Moral injury’, where people experience distress through actions (or inaction) that violates their moral or ethical code (Greenberg et al., 2020), has been noted in social care, and social care organisations should seek to respond to and prevent moral injury as far as possible (Reamer, 2022).

These factors – overwork, ethical stress, empathetic distress, moral injury – are likely to be contributing to the current workforce issues in adult social work. In September 2022, 11.6% of social work posts in local authorities’ adult services were vacant, with turnover standing at 17.1% (Skills for Care, 2023).

What you can do

If you are in direct practice: You may feel like you have little control over wider forces, such as austerity and the cost of living crisis, and limited options available for people you work with. The More Resources, Better Used group said they “know the issues for social work are at a higher level than those controlled by the individual social worker” and needed to be addressed at an organisational level. However, the group wanted social workers to feel empowered to do what was within their control. To “feel joy in their work, and be able to contribute to a compassionate culture.”

Hopefully, it is heartening to read that people value what social work can offer. This may encourage you to think of the power you do have and how you might use it. How can you use the time you do have with people to the fullest? What do they specifically value in the work you do, and how can you maximise this in the time you spend together? Who do you need to talk to if this involves a different balance in your workload?

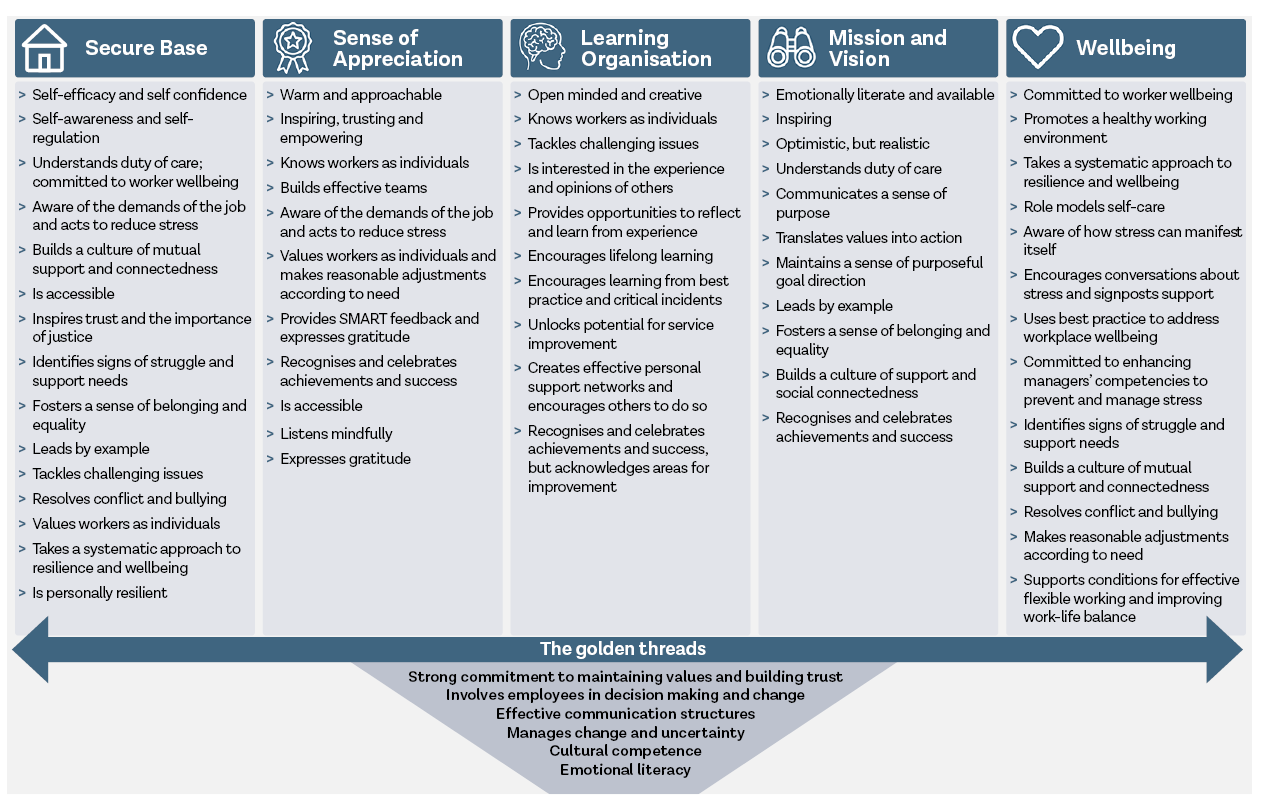

If you are a leader or manager: It’s crucial that organisations consider resilience within social work. The SWORD (Social Work Organisational Resilience Diagnostic) project has found five dimensions that are associated with social work organisational resilience:

(Grant et al., 2022)

SWORD five dimensions enlarge view.

Research in Practice regularly offers participation in SWORD (Social Work Organisational Resilience Diagnostic), which is designed to help leaders and managers create the conditions to sustain and develop resilience according to a tailored evaluation of each of these five dimensions. This is a free service for all organisations who are part of the Research in Practice network. In addition, there is a freely available SWORD Workbook that outlines several tools and reflections for organisations.

Further information

Read

Chris Perry, a former director of Social Services, reflects on social work value as a resource in Change Agents, Not Gatekeepers on BASW’s website.

Watch

A series of three videos on Supporting emotional resilience in social work is available on the Research in Practice website.

BASW has a webinar on resilience and wellbeing in social work. This includes looking at local authorities where recruitment and retention of social workers has been a positive experience.